Celia Salazar

Colectivo de Mujeres

(Collective of Women)

El Alto, Bolivia

“We were in the streets 12 days with nothing to eat and we had to

feed our children.”

Roots

Celia Salazar was born into a mining family in rural Bolivia. She lost both her

parents to the mine—her mother to lung disease, her father to an accident.

She migrated to El Alto and focused on raising three children until a stint

as block captain drew her into neighborhood organizing. As she scored small

successes on modest infrastructure projects, she rose through the ranks of

local politics.

Journey

Working at the Gregoria Apaza Women’s Center in El Alto, Celia met other

Alteña (from El Alto) leaders, many of who had experienced discrimination and

even sexual abuse because of their positions as community organizers. To

combat this, Celia helped forge a partnership between City Hall and Gregoria

Apaza to create a leadership school funded by the municipality. Many of the

women involved experienced growing confidence. When a woman would come

to the group having been beaten by her husband, the members went to her

house and spray painted “aggressor” and “wife beater” on the walls in order to

shame the husband. Many involved women also divorced their husbands,

including Celia. “As a single mother, I began to confront the challenges of

life,” Celia proudly claimed.

Leadership

Celia helped found the Colectivo de Mujeres and began to organize around

natural resource issues. When the Bolivian president moved to export Bolivia’s

natural gas supplies, Celia and her colleagues took to the streets in July, three

months before the mass mobilizations in October

2003. They used homemade

fliers and spray painted messages to educate El Alto about the negative impact of natural gas privatization. The protests grew to envelop the whole city and Celia was on the front lines of this mobilization, organizing barricades, marches, and communal kitchens. Despite over 65 deaths of El Alto civilians during clashes with the state, the mobilization ousted the president and halted his export plan.

Portraits &

Biographies

Isabel Atencio

Colectivo de Mujeres

(Collective of Women)

El Alto, Bolivia

“I love to serve my community. These are my

best days as a leader, getting things done,

working under a friendly government.”

Roots

Having lost her parents as a child, Isabel Atencio

was raised by her grandmother in Tembladerani,

in the state of La Paz, where she finished high

school and married at age 18. When Isabel

moved to El Alto in 1985, the informal houses

in her neighborhood were just walls, lacking both

floors and roofs. This motivated her to get

involved and work for improved housing

and infrastructure.

Journey

Isabel and her neighbors began to organize to

purchase the land titles at a cheap price. The struggle took 18 years, but between 1986 and 2004 they managed to reduce the average lot price by 98 percent from an impossibly high $15,000 to a bargain price of just $300. After attending the Gregoria Apaza leadership school in 2002, Isabel helped form the Colectivo de Mujeres to address issues such as women’s political participation, self-esteem, and natural resource privatization. The group disseminated information through a self-published newsletter.

Leadership

During El Alto’s battle for natural gas in October 2003, when hundreds of thousands of Alteños mobilized, one of the first battles was on Nestor Galindo Street in front of Isabel’s house. Neighbors blockaded the street to stop soldiers from transporting natural gas through El Alto and violence ensued between neighbors and soldiers. In 2010, Isabel finished her fourth two-year term as neighborhood president. She represents about 1,500 people and continues to focus on infrastructure development.

Luisa Crespa

Executive Council of the Federation of Neighborhood Councils of

El Alto (FEJUVE)

El Alto, Bolivia

“I’m not that kind of woman. I speak out. I went to the Aguas Illimani

[water company] offices. I petitioned. I learned and discussed. I did the work.”

Roots

Born near El Alto’s Centro Minero Corquiri, Luisa Crespa spent her childhood

in poverty, initially without water or electricity. From her parents, who co-founded

the community of Urbanización Corquiri in 1988, Luisa learned the importance of

community activism. After receiving leadership training from Gregoria Apaza,

she became politically involved, serving as neighborhood secretary until her

neighbors pushed her to run for neighborhood president.

Journey

As neighborhood president, Luisa attended the 2002 Congress of the Federación

de Juntas Vecinales de El Alto (FEJUVE). Scanning the list of delegates, Luisa

bristled when she saw that she— the only woman among her district’s 20-person

delegation—appeared dead last on the list. She tore the list to shreds and

“requested” a new list. In 2003, Luisa led her neighborhood’s participation in

the historic “gas war” revolt that paralyzed La Paz and forced the government

to change its natural gas policy.

Norah Quispe

Citizen Action, Center for the Promotion

of Women Gregoria Apaza

El Alto, Bolivia

“The effort we put into our work wasn't from one

person, but from all of us women, put in with a

lot of love and a lot of commitment.”

Roots

Norah Quispe grew up listening to her grand-

parents’ stories about the meaning of being an

indigenous Bolivian and learning the value of hard

work and education from her mother. One of her

strongest childhood memories was when the

Bolivian military conscripted the young men in

her neighborhood for combat in conflicts that

Norah’s family opposed. After finishing high

school in 1989, Norah worked with Aymara

health care practices at the Centro de Cultura

Popular and, in 1991, began studying social

work at the Higher University of San Andrés,

supporting herself by working a night job.

Journey

When working in a tuberculosis-afflicted neighborhood, Norah was strongly affected by the unnecessary deaths of the poor, who could not access medical care. A Peruvian conference about 500 years of resistance to colonial domination and sexism further politicized Norah. She became skeptical of social justice groups that preached gender equality, but treated female members as second-class. Beginning in 2001, Norah worked for the Aymara Amuyt’a Women’s Development Center, allowing her to reconnect with her Aymara heritage and language and helping her develop her public voice through newspaper and radio journalism.

Leadership

Norah left her position as president of Aymara Amuyt’a in 2007 to work for Citizen Action, an NGO that provides job and leadership training to women. She emphasizes the inclusion of working women at the grassroots and giving equal attention to the needs and contributions of women in urban and rural organizations. Norah is currently working toward an M.A. in Sociology of Socioeconomic Development from the Institute of Sociological Research, where she focuses on urban movements and the political ideology and participation of indigenous women. She plans

to start her own organization to support indigenous people.

Benita Pari

Director of the Unidad de Mujer (Office of Women)

El Alto, Bolivia

“I want to work with the grassroots—with all Alteña women.”

Roots

Born in 1977, Benita Pari moved from the Altiplano (high plains) to

El Alto when she was 20 years old. She could not yet speak Spanish

and the transition was difficult, but she worked hard to finish her basic

studies in a night school, and received her high school equivalent degree

in three years. During this time, she also worked in an almond factory

with 170 other women.

Journey

In 2000, Benita worked for Integral Services for the Development of

Women, where she supported gender equality and municipal affairs

programs. Because of her low level of education, however, Benita did

not feel confident in her position. Benita’s boss encouraged her to pursue

higher education in Aymara studies. Her father was not supportive,

stating that women should work in the home, but Benita nonetheless

decided to attend the Higher University of San Andrés.

In the 2002 elections, Benita worked for a legislative candidate from the

Movement of the Revolutionary Left. Although he lost that race, he later

became Prefect of La Paz, and hired Benita as a secretary to coordinate

work between La Paz and the surrounding provinces. In 2006, Benita

was hired to teach Aymara to government officials, a position

that acquainted her with the workings of the municipality.

Leadership

In 2008, the mayor of El Alto, Fanor Nava Santiestevan, offered Benita the

position of director of the Unidad de la Mujer de El Alto, a governmental

organization that offers legal services and counseling to women. Benita’s

team includes a social worker, a psychologist, an attorney, and a manager.

She oversees two offices, which serve 400 clients per month, mostly victims

of domestic violence. Benita is developing domestic abuse prevention and

educational programs, a task she says is difficult in the machista El Alto society.

Rosa Queso

Coordinator of the Unidad de Mujer (Office of Women)

El Alto, Bolivia

“The land and my people are the source of my strength.”

Roots

Rosa Queso is from the rural province of Ingavi and immigrated to El Alto in

1986 seeking a better life. In 1987, she experienced a bad fall, and was

hospitalized for a year. She believed that she would never walk again, yet

has made a nearly full recovery. After recovering from her injury, Rosa began

working with women’s organizations that focused on gender equality, domestic

violence, and supporting indigenous women and artisan groups.

Journey

In 1989, Rosa worked as a technical training teacher with the Pachamama

Women’s Center, where she was responsible for implementing workshops

about gender equality and domestic violence. She also held workshops about

women’s rights and domestic violence. Rosa then became the leader of her

neighborhood organization in the Atalaya zone of El Alto, and served two terms

as president of Atalaya (2004-08). In 2006, Rosa was elected vice-mayor of El

Alto’s fifth district (population 90,000). Among 49 candidates, Rosa was the

only woman.

Leadership

Rosa now works at Unidad de la Mujer, a department of the municipal

government of El Alto, where she focuses on domestic violence prevention

and on providing legal services to people who have experienced domestic

violence. Despite these efforts, Rosa has observed an increasing rate of

domestic violence. Her office sees about 25 people a day, mostly women,

who have suffered from domestic violence. Rosa is also pursuing an M.A.

in social work.

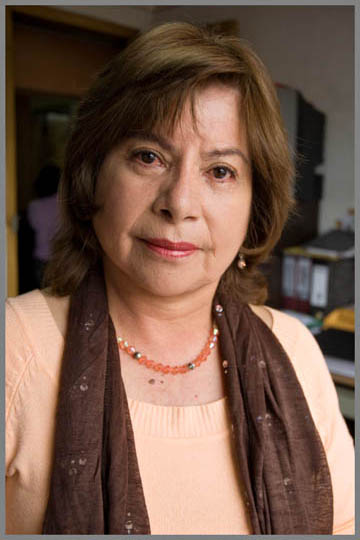

Rosa Rodríguez

Spokesperson for the Coalition in the Defense of Water

Quito, Ecuador

“For me, involving myself in processes of social change was not a major shift,

since that was the lifestyle I believed in, treating people as compañeros. It was

perfectly normal.”

Roots

Rosa Rodríguez grew up in rural Ecuador where her father engaged in human

rights activism with campesino and indigenous communities. Rosa, who

is mestiza, spent a great deal of time in the homes of indigenous people.

This experience radicalized her, through exposure to the racism and

economic injustices that Ecuador’s indigenous population face daily.

Journey

As a university student in the 1970s, Rosa became active on issues of

unionization. She organized campaigns to support victims of political violence

in Nicaragua and El Salvador. During the repressive era of President Febres

Cordero (1984-88), she helped found Ecuador’s Alfaro Vive Carajo guerrilla

movement. During what she called her “subversive period,” Rosa was jailed

for a year, and some of her compañeros were murdered. Her journey next took

her to Uruguay, where she worked in an activist cooperative, working in radical

radio and print journalism. In 1992 she returned to Quito to participate in

Ecuador’s indigenous uprisings against neoliberalism.

Leadership

In 2004, while working for the alternative newspaper Tintají, Rosa researched

the mayor’s plan to privatize water services in Quito. Rosa published an article

exposing the plan, and challenging PricewaterhouseCoopers’s analysis of costs

and benefits. Rosa’s article proved pivotal in the creation of the Coalition in

Defense of Water, a non-hierarchical alliance of organizations that defeated

the privatization plan. Rosa served as a key organizer and the spokesperson

for the Coalition during this 2004-07 battle. She now directs Ecuador’s chapter

of an International NGO.

Blanca Chancoso

Director of the Dolores Cacuango

Women’s Leadership School, Ecuarunari

Quito, Ecuador

“I was going to create in myself a thought, a spirit

of action on behalf of my people, to demonstrate

the values of my people.”

Roots

Blanca Chancoso is one of the most revered

indigenous activists in Ecuador. She has worked

in the indigenous movement since 1970, gaining

international recognition for her work for equality.

Blanca comes from a family of agricultural

workers. They were laborers on an hacienda

(ranch) in the province of Imbabura. Her father

was the only person in the family who attempted

to liberate himself from this life by working in

construction. She grew up with the “spirit of a

rebel,” wanting to help her people and valuing

her indigenous heritage.

Journey

In 1973, Blanca earned an education degree and became a teacher. She observed that indigenous students were vulnerable to abuse and exploitation due to racism and their lack of Spanish. Blanca began to organize the community, holding meetings to recapture the value of indigenous people and resolve problems internally. While indigenous community members supported her activism, some non-indigenous community members persecuted her, and tried to drive her out. As word of her activism spread, however, she gained a reputation as an effective organizer. She decided to stop teaching and focus entirely on the battle for indigenous rights.

Leadership

Blanca’s trajectory as an activist quickly led her to the highest echelon of indigenous power in Ecuador. She co-founded the Indigenous Federation of Imbabura, a group that merged with the mass indigenous organization Ecuarunari, where she served as Press Secretary, Health Secretary, and then Secretary General, a post she held for two terms, in 1979-83 (in 2010, she was still the only woman to have held the top executive position). In 1986, she helped found, and was the first Director, of the powerful Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE); she held key posts over the next two decades. Since 2003, Blanca has led the Dolores Cacuango Women’s Leadership School, which aims to empower communities by empowering women. Blanca is frequently cited as one of the most powerful women in Ecuador.

Magdalena Aysabucha

Director of Women and Family, Ecuarunari

Quito, Ecuador

“As a woman, I will not lower my voice.”

Roots

Magdalena Aysabucha has been active in fighting for women’s and indigenous

rights since 1986, when she directed a potable water project in her community

of San Pablo de Santa Rosa in the Ecuadorian province of Tungurahua.

Magdalena identified water collecting as one of her community’s most pressing

priorities and, after organizing eleven indigenous communities in the Sierra to

participate, successfully implemented the Francisco Gangotena piped water

project, which now serves thousands of people.

Journey

In 1990, Magadalena formed a women’s group that started a communal

micro-finance bank. The women worked on a donated farm and as artisans,

generating sufficient funds to provide small credits and loans to women. Despite

experiencing sexism and machismo from male members of the community,

Magdalena and the women’s group continued to fight for women’s rights.

Recognized for her work as a community activist, Magdalena became president

of San Pablo de Santa Rosa’s 180 families. This activism complemented her

involvement in the national indigenous movement. She attended the Dolores

Cacuango Women’s Leadership School and also attended international meetings

for indigenous rights.

Leadership

After graduating from Dolores Cacuango in 2005, Magdalena was elected to the

position of Leader for Women’s and Family Issues for Ecuarunari, an indigenous

organization representing 500,000 people throughout the Ecuadorian Sierra.

Magdalena is in charge of programs in fourteen provinces; each sends a

delegate to the leadership council. She works with the Dolores Cacuango

school, educating and empowering women leaders. The school promotes

agricultural productivity, holds artisan fairs, and has opened childcare centers

throughout the Sierra. Magdalena states that she will continue to fight for equal

rights for women and men within Ecuador.

María Hernández

President of Mujeres por la Vida (Women Struggling for Life)

Quito, Ecuador

“[With the new Ecuadorian constitution], now we fight with the law on our side.”

Roots

At age 14, María Hernández began her political involvement through a Christian

youth group in her Quiteño neighborhood, Menadoz. As a high school student,

María worked nearly full-time in community organizing. She helped form the

Unión de Mujeres Taki, which conducted youth education about women’s health.

María became pregnant as an adolescent and she marks the birth of her son as

the most important moment in her life. Though parenthood forced her to postpone

her education, it also renewed her commitment to activism on behalf of

mothers

and their children.

Journey

In 1988, military forces killed a child from María’s neighborhood during a political

protest, galvanizing her into political action and leadership posts within the

Coordinadora Popular de Quito. In 1995, María co-founded the illegal land

invasion settlement of San Juan Bosco de Itchimbía; she led the community

from 1996 to 2006. Under María’s leadership, Itchimbía pioneered ecologically

sensitive strategies for self-help housing and employment. In 2004, her

successful neighborhood-level activism culminated in her election as a

vice-councilwoman on Quito’s Metropolitan Council.

Leadership

Now the president of the national organization Mujeres por la Vida (MPLV),

María was a vocal advocate for women’s rights during the 2008 Constituent

Assembly and the successful campaign to approve the Constitution. She helped

draft proposed articles that recognize women’s domestic household work as

legitimate work meriting retirement and social security benefits. Despite these

gains, she laments Ecuador’s continuing failure to recognize abortion access as

a legal and protected right. Under her leadership, MPLV has become the

backbone of Foro Urbano, a rapidly expanding political organization that

played a key role in negotiating the new Constitution. Despite the more

expansive scope of her current political agenda, María’s political activism

remains rooted in women’s needs.

María Quispe

Director of Leadership Training, Mujeres por la Vida (Women

Struggling for Life)

Quito, Ecuador

“There I was in the house… but I was missing something.”

Roots

Since her youth, María Quispe has been involved in her Quito community of

Pichincha, dedicating her self to improving the standing of women in Ecuador.

María’s politicization developed while providing summer camp opportunities

for poor children. She served as a community leader, eventually becoming

secretary and then president of her community. María was also a member of

a theater group supported by City Hall, providing educational programming to

as many as 2,000 teenagers and 8,000 children. This youth movement played

an important role in stopping political oppression by President Febres

Cordero (1984-88).

Journey

Combining her work experiences in poor neighborhoods in Pichincha and her

studies of leftist political processes in Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Cuba led

to María’s political radicalization. After working with Quito’s youth movement,

she worked from 1992 through 1998 with indigenous movements in Chimborazo

(in southern Ecuador) alongside Monsenior Leonidas Proaño, the “bishop to the

poor.” At this time, María began strongly identifying with women’s struggles

against discrimination, and especially indigenous women. She actively opposed

discrimination based on gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status while

following and implementing the tenets of liberation theology.

Leadership

Today, María leads personal development and support programs for Mujeres

por la Vida and Foro Urbano. She organized a political leadership school for

women, focusing on gender identity, feminist movement theory, national

history since the conquest, democracy, development, organizing, and

leadership. Each participant is encouraged to develop her personal leadership

style and connection with her community.

Sara Proaño

Director of Public Health, Foro Urbano (Urban Forum)

Quito, Ecuador

“We are creating a new vocabulary that makes us become visible.”

Susana Reyes

Dancer & Choreographer

Quito, Ecuador

“The new constitution is not perfect, yet implies great possibilities for

constructing a society that is truly human, and provides a great inspiration

for everyone… It represents a recapturing of ancestral patterns of thinking

and living, integrated into the present. It is practical while based in

communitarian values… It is a profoundly post-colonial constitution.”

Roots

Susana Reyes was born into a cooperative of washerwomen in an

impoverished and often violent community in central Quito. Even as

a child, she felt a powerful compulsion to create dance and theater.

“The women I grew up amongst suffered so much,” she said, “yet

were so strong; my mother was a leader.” With merit scholarships,

Susana studied dance and art at university and professional levels.

María Augusta Calle

Chair of the Constituent Assembly Committee on Sovereignty

Quito, Ecuador

“This is the beginning of a very painful revolutionary process. It is more difficult

to create a revolution with peace than with weapons.”

Roots

María Augusta Calle has been involved with a range of social movements since

she was 18, including multi-ethnic indigenous movements such as CONAIE and

El Comité del Pueblo (Committee of the People), environmental groups, activist

communications coalitions, and with international populist and anti-authoritarian

journalism movements across South America. She is also a successful

mainstream television journalist and commentator.

Journey

Today María is the director of the TeleSur network in Ecuador. In 2008, the

right-wing newspaper El Comercio accused her of ties to Colombia’s FARC

rebel group. María believes the charges were based on her principled and

long-held opposition to Plan Colombia, the US military and anti-drug program

within Colombia, that also impacted Ecuadorian sovereignty. Plan Colombia

includes aerial fumigation of wide regions of Colombia and Ecuador, resulting

in the injury of people, animals, and the environment. María believes Plan

Colombia is part of a larger US plan to dominate Latin America, stripping

and exploiting its natural resources, including petroleum, minerals, forests,

and water. She denied the newspaper’s charges, and she countered with

an anti-defamation lawsuit. María won the lawsuit, clearing her name

and reputation.

Monica Chuji

Chair of the Constituent Assembly Committee on Natural Resources

and Biodiversity

Quito, Ecuador

“There needs to be an equilibrium, we should think about a post-petroleum

economy, we should think about a post-extractionist economy.”

Roots

Searching for employment, Monica Chuji’s family migrated from their

impoverished indigenous community in southern Ecuador to a northern

petroleum-extraction region. From early childhood, she accompanied her

parents to community meetings, where she learned about the importance

of Ecuador’s land and natural resources, and the indigenous understanding

of nature as a living force with its own rights. From local clergy, Monica

came to understand that the survival of Ecuador’s indigenous population

and traditions would require self-organization and initiative, and would not

easily be granted by conservative social and economic forces that had

dominated Ecuadorian society for centuries.

Journey

Monica quickly ascended to local leadership positions and joined CONAIE.

She was an active participant and young leader in the 1990 indigenous uprising

that thrust issues of indigenous rights and demands onto Ecuador’s national

stage. Inspired by the results of the 1990 protests, Monica participated in

additional mobilizations in 1992 and 1994. She came to believe that indigenous

stories needed to be told in indigenous languages, and she helped organize

an indigenous film festival. That festival opened a pathway of educational

opportunities for Monica and others. Monica studied environmental issues in

university courses in Ecuador and she won a scholarship to study indigenous

rights in Spain. Subsequently she was hired by the United Nations to work

internationally on inter-cultural and indigenous rights.

Leadership

In 2006, President-elect Rafael Correa asked Monica to serve as his press

secretary. She worked for President Correa until the 2007 election of a more

progressive Constituent Assembly. She successfully ran for a seat on the Constituent Assembly, chartered to write Ecuador’s new constitution. Monica was then elected to lead the Committee on Natural Resources and Biodiversity. She chaired this committee during eight months of deliberations over several of the most crucial constitutional articles. These included the prohibition of all forms of water privatization and the constitutional recognition of the inherent rights of nature. The 2008 Constitution requires that the government must consult, negotiate with, and compensate with indigenous peoples about resource extraction on their traditional lands—but it does not require the government to obtain their consent before authorizing resource extraction, as Monica Chuji would prefer.